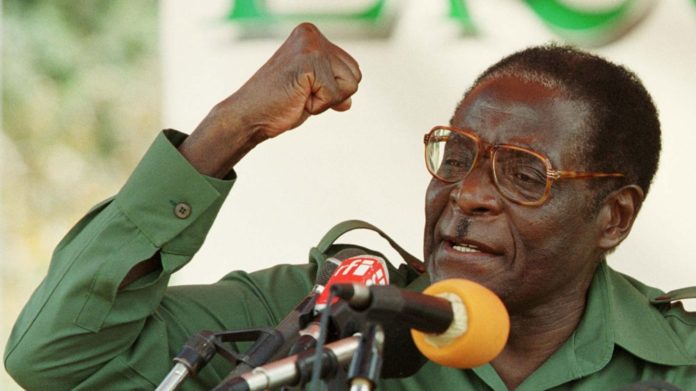

Zimbabwe’s former president Robert Mugabe, who ruled for 37-year has died at the age of 95.

Mugabe was the caricature of an African dictator who oppressed his opponents and ruined a country to retain power, which he was forced to relinquish, at the age of 93, in 2017.

Rumors had swirled around the health of the ex-president, who spent months in a hospital in Singapore earlier this year. Details of what ailed him were a closely guarded secret.

A former teacher, Mugabe was imprisoned for ten years for opposing the white-minority government of Rhodesia (as Zimbabwe was known before independence). After his release, he orchestrated a guerilla war which won freedom for his country in 1980.

As Zimbabwe’s first prime minister, he was at first lauded internationally for building schools and hospitals.

However, the former champion of one man, one vote soon mounted a brutal crackdown against the opposition led by the late nationalist politician Joshua Nkomo. For decades, he maintained his grip on the country with the support of the army and a series of controversial elections.

His late rule was marked by the violent eviction of thousands of white farmers and increasingly dubious elections, including one in 2008 which he lost to Morgan Tsvangirai, sparking political violence that human rights groups say claimed over 200 lives.

Widely seen as a disgraced aging despot desperately clinging to power, Mugabe’s rule finally came to an end after he sacked his longtime ally, Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa, so that his much younger wife Grace could succeed him.

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was born on February 21, 1924, at the Roman Catholic Kutama Mission, Southern Rhodesia. His father, Gabriel Mugabe, was a carpenter and his mother, Bona, a catechism teacher.

After elementary school he entered a teacher training college, going on to work in several schools in Rhodesia before winning a scholarship to the University of Fort Hare in South Africa, where he read history and English.

In 1952, after graduating, he returned to teach in Rhodesia, later moving to Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Ghana, a period during which he accumulated more university degrees, and met his first wife, Sally Hayfron.

In 1960, he returned to Rhodesia and worked as publicity secretary for the newly founded anti-colonialist, African nationalist National Democratic Party. Quickly rising in influence, he advocated violence to end white rule, co-founding the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) with Ndabaningi Sithole in Tanzania after fleeing Rhodesia.

He and his comrades insisted the white leadership was illegitimate, had occupied his people’s land and made them “a race of no rights beyond those of chattel.”

In 1963, he returned and was arrested for making subversive statements. He spent almost eleven years in jail, during which time he continued his political activism and study, earning university degrees in education, economics, administration and law.

After his release in 1974, he led the ZANU-PF, the guerilla movement, from Mozambique against Premier Ian Smith’s white minority rule.

When the war ended in 1979, Mugabe was hailed as a war hero at home and abroad.

He went on to lead the newly independent Zimbabwe — as prime minister from 1980 to 1987, when he became its president.

Articulate and smartly dressed, Mugabe came to power commanding the respect of a nation.

He had a strong head start, inheriting a country with a stable economy, solid infrastructure and vast natural resources. But the descent into tyranny didn’t take long.

His hardline policies drove the country’s flourishing economy to disintegrate after a program of land seizures from white farmers, and agricultural output plummeted and inflation soared.

At first, Mugabe preached reconciliation with former enemies at home and abroad. For the country’s black majority, Mugabe built schools and hospitals and promoted agriculture for peasant farmers.

He was lauded by the West as a new kind of African liberation leader, particularly by former colonial ruler Britain, which had refused to recognize Smith’s government and leveled economic sanctions against the country.

But early on in his rule, Mugabe showed a penchant for dealing with opponents ruthlessly. The most startling example was the Gukurahundi killings between 1983 and 1987.

Mugabe was accused of leading the massacre against political opponents. Tens of thousands of ethnic Ndebeles were killed — including many found in mass graves that the victims reportedly had to dig themselves.

His reputation for ruthlessness stemmed from this period. Later Mugabe would boast of having a “degree in violence”.

Despite the turmoil, Zimbabwe’s economy was strong in the early years of Mugabe’s rule. The country was known as the “breadbasket” of southern Africa and showed startling improvements in literacy rates.

But the tone began to change in 1987 when Mugabe consolidated his power, assuming the office of president and head of the armed forces. In 1990, the government began to amend laws allowing it to purchase land for resettlement and redistribution, prompting objections from landowners and the US and UK.

As land-grabs escalated, the economy began a downward spiral in 1995 that culminated in catastrophic hyperinflation. Mugabe’s government faced charges of elitism, cronyism and corruption.

In 1996, he married his former secretary, Grace Marufu (following the death of his first wife in 1992). Elections that year became a one-man contest, after all other opponents dropped out days before the poll.

In 2000, Mugabe and his ruling ZANU-PF party suffered their first major defeat since coming to power. Voters rejected a new constitution, handing the longtime president an unexpected blow in what was widely considered a confidence vote on his government.

The rejection emboldened the newly formed opposition party, Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), but it also prompted Mugabe to take drastic measures to stay in power.

As the economy continued to worsen, Mugabe gave his blessing to roving bands of so-called war veterans to embark on often violent seizures of hundreds of white-owned farms they claimed had been stolen by settlers.

Mugabe called the land battle “The Third Chimurenga,” deliberately linking the farm seizure program to Zimbabwe’s struggle against colonial rule.

Many of the farms were turned over to Mugabe’s cronies, who subsequently did not harvest the land, further contributing to Zimbabwe’s economic collapse. International aid and foreign investment dried up in the wake of the land-seizure program, and the US and European Union imposed economic sanctions on the country.

In the following years, his government charged the MDC’s leader Tsvangirai with treason and passed increasingly tough laws aimed at stifling the independent media and public dissent.

In 2007, the University of Edinburgh withdrew the honorary degree it awarded Mugabe in 1984 for his services to education in Africa. In 2008, the UK stripped him of his 1994 knighthood and the University of Massachusetts Board of Trustees revoked the honorary law degree it gave to Mugabe in 1986.

But at elections marred by deadly violence and accusations of vote rigging in 2008, Mugabe was forced to concede some of his power. The MDC won a majority of seats in the parliamentary vote, claiming also that Tsvangirai had secured more than 50% of the presidential votes as well.

Mugabe claimed victory, but he was forced to hold talks to resolve the ongoing political dispute. Tsvangirai accepted the post of prime minister in a power-sharing deal negotiated by South Africa — though claims of ZANU-PF harassment and violence against opposition politicians persist to the present.

Despite Zimbabwe’s deepening economic crisis, Mugabe continually rebuffed calls to step down, insisting he would leave office only when his “revolution” was complete. That, he said, meant until the end of his days on earth: “Only God who appointed me will remove me — not the MDC, not the British.”

He focused his ire on the economic sanctions imposed by the United States and the European Union, which he said were “unjustified” and “illegal” and intended to bring about regime change.

In 2010, he was nominated by his party to run for the presidency again. However, the 86-year old was reportedly making regular trips to Singapore for medical treatment.

Despite this, Mugabe, appearing as politically strong as ever, was re-elected with a solid majority in 2013, ending the power-sharing agreement signed in 2008. Tsvangirai alleged widespread fraud.

However, in 2014 signs of dissent emerged among his loyalists. Mugabe fired his deputy Joice Mujuru, a few hours after she dismissed allegations that she’d plotted to assassinate Mugabe as “ridiculous”. Zimbabwe’s Chief Secretary to the Cabinet Misheck Sibanda said that Mugabe also fired eight Cabinet ministers.

In November 2017, Mugabe finally came unstuck when he fired Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa, to clear the way for his wife, Grace Mugabe, to succeed him.

A week later Zimbabwe’s military leaders seized control, placing Mugabe under house arrest and deploying armored vehicles to the streets of the capital, Harare. On November 21, 2017, Mugabe resigned as Zimbabwe’s president after 37 years of autocratic rule.

In his ‘retirement’, Mugabe was rarely seen in public, instead spending his time between Singapore, where he received medical treatment, and his plush 25-room Blue House residence in Harare.

Sightings of his wife, nicknamed “Gucci Grace” for her love of a lavish lifestyle, became similarly scarce. The couple were criticized for their luxury lifestyles as the country was plunged into

economic ruin.

He celebrated his 85th birthday with an opulent party that cost a reported $250,000 and continued to hold such birthday events annually, last year spending a reported $800,000 and celebrating in a region suffering drought and food shortages.

He repeatedly rebuffed repeated calls to step down, insisting he would only leave office when his “revolution” was complete.

“This is a man who had so much to offer to Zimbabweans, but he didn’t, he focused on himself,” said Trevor Ncube, one of the country’s most powerful publishers.

Source:CNN